New Works

October 2022, EBONY/CURATED, Franschhoek

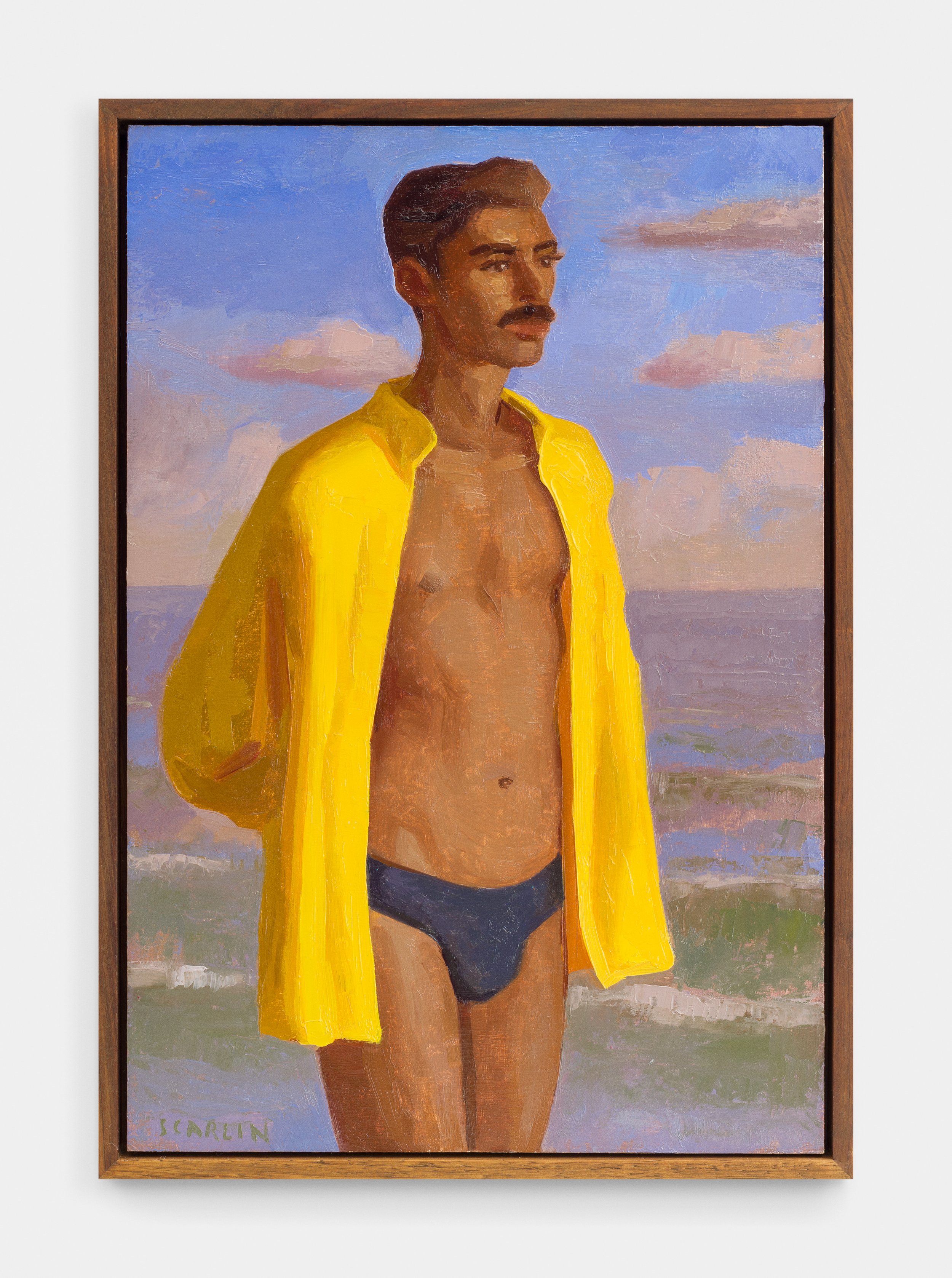

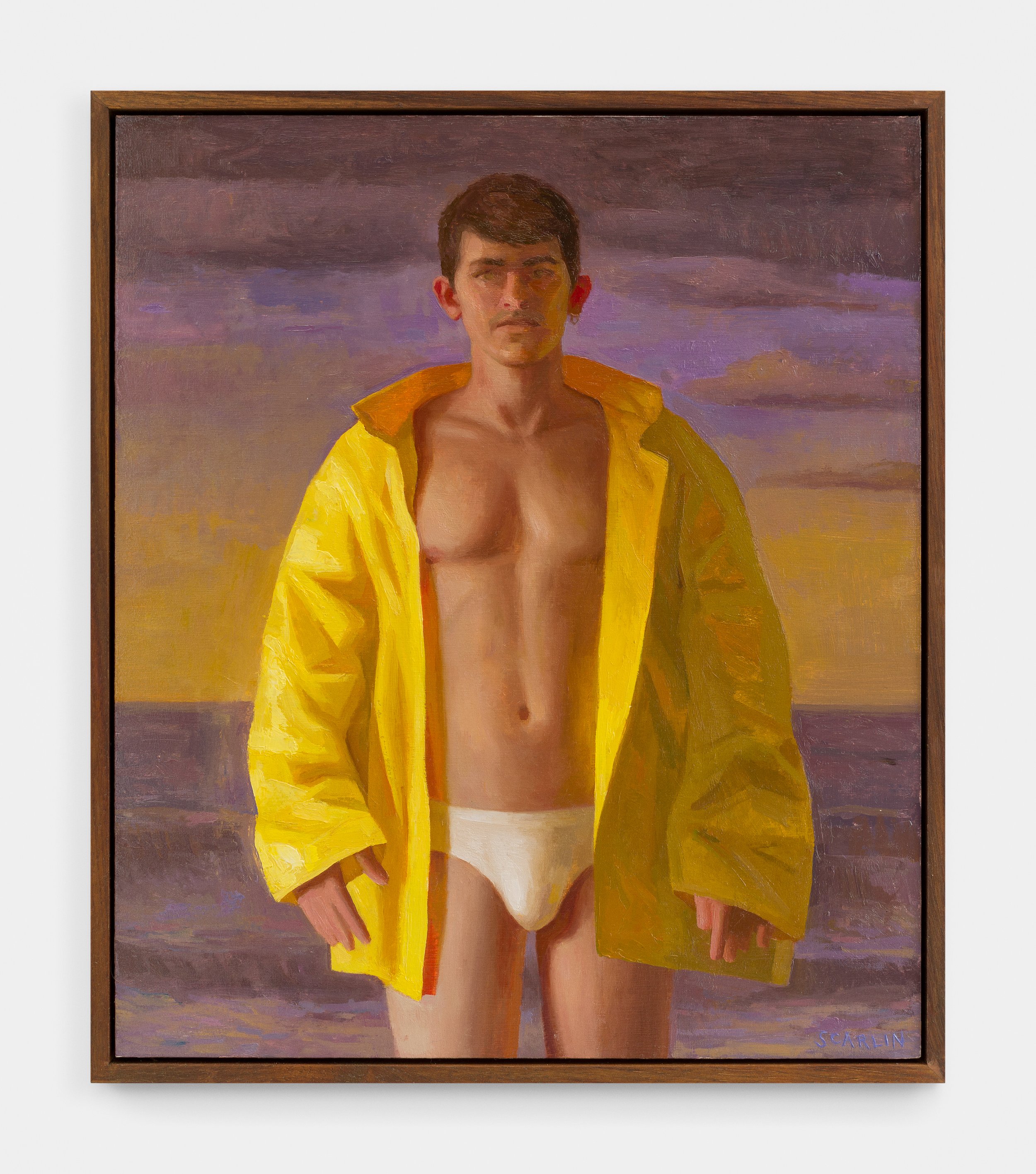

Oliver Scarlin’s “New Works” invites the viewer into a privileged gaze on normally private scenes of domestic intimacy. These vignettes are playfully imagined in a curation of portraits, self-portraits, still-life paintings and ceramic works. While Scarlin’s earlier work distils the story of falling in love, these new works continue to capture the artist’s life with his partner and objects within the home. Here, however, we are also witness to an emergent imagining of queer love beyond a heteronormative couple-form, gesturing at forms of queer collectiveness and falling in love with queerness itself as a mode of being and living. This philosophy of community-building is replicated in the various mediums of the collection – paintings and ceramics and ceramics within paintings – as objects that exist in harmony, as symbolic echoes throughout various works or as actual, tangible objects.

The defining mood that binds these various works and mediums together is therefore one of togetherness and optimism, signalling a period of transition and reflecting on embracing colour and joy. A vibrant palette of yellow, turquoise, and orange threads through portraits, self-portraits and still-life images and embodies this mood of sanguinity, while ceramic works like “The Three Gays, Sis” embody its embrace and the forms of unity that’s made possible by its reach.

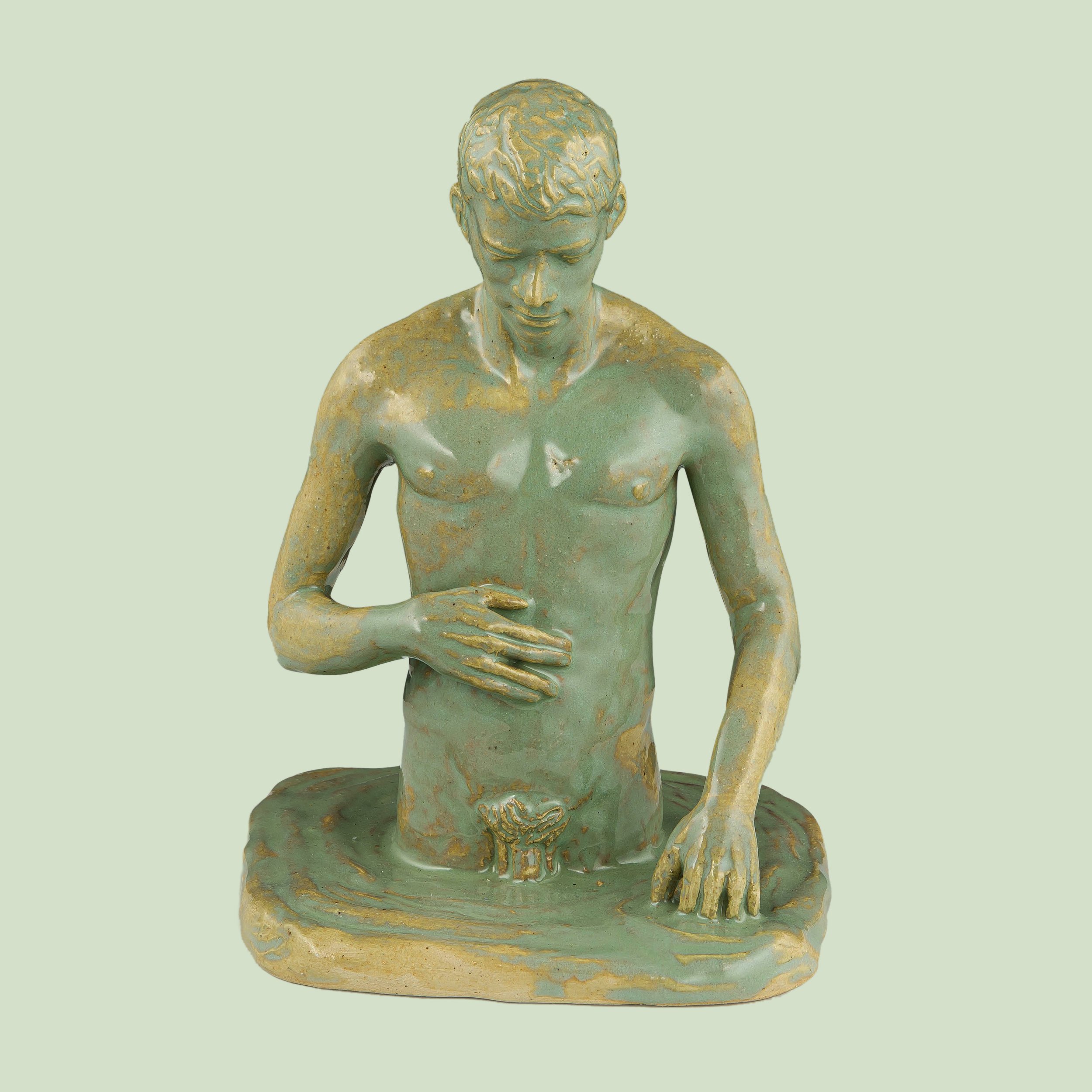

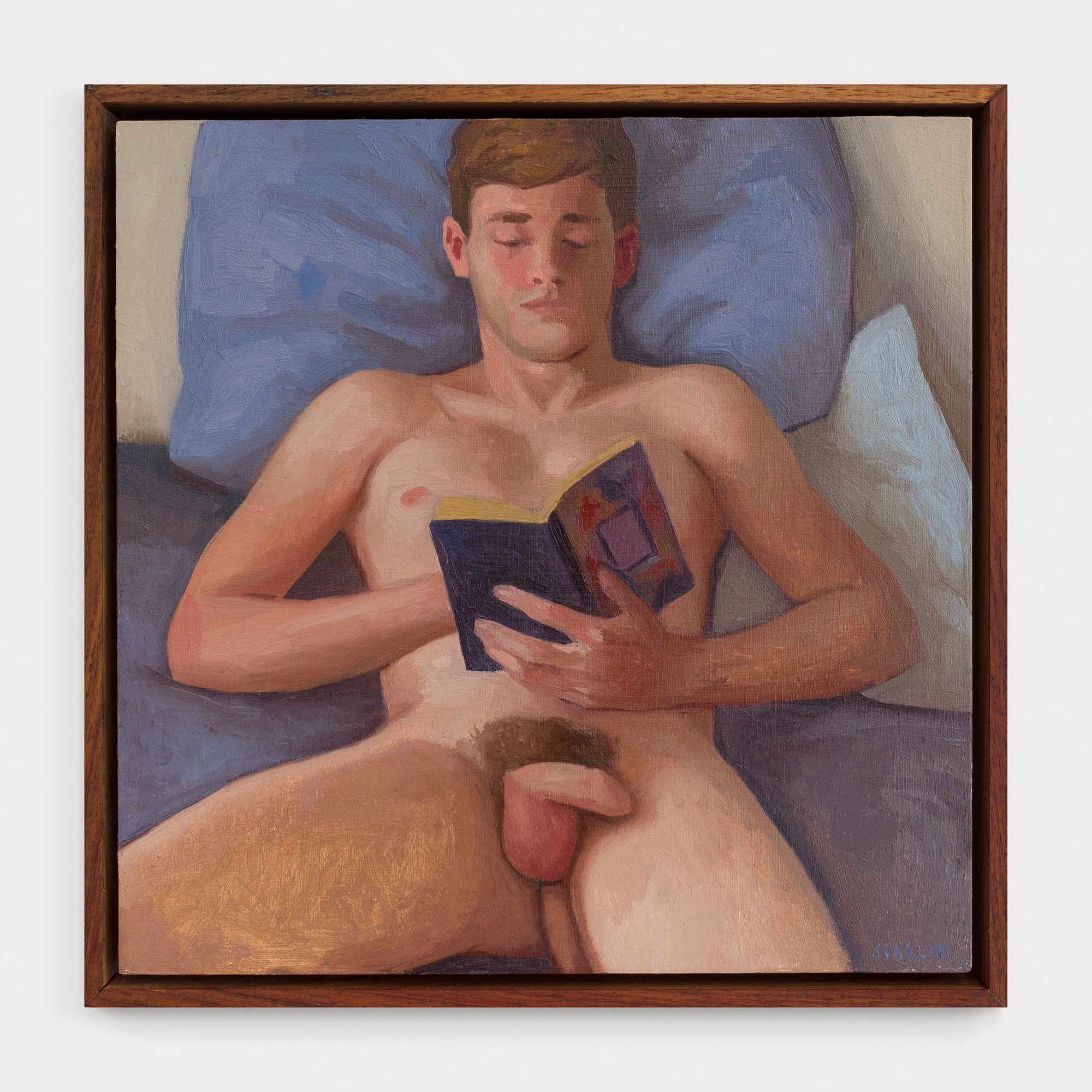

In this spirit, each figure or painting is made from life, in intimate sittings between the subject and the artist – also reflecting this movement between scenes of domestic intimacy to other forms of collectivity that are also intimate. However, these images don’t aspire to realism but, rather, act as a layer between imagining and reality. Resisting the urge to flatten, these works rely on texture instead. The textures of various fruits, naartjies, papaya, plums, quinces are vividly captured and colourfully rendered, and are also the fleshy things in still-life paintings that connect with the flesh of bodies in various portraits. The fragile texture of paper cups contrasts the rubbery glove or the delicacy of a ceramic vessel. It’s especially poignant then that the artist handmakes the ceramics depicted in images, so that the same hands that form the dainty, breakable objects also make them undying, and both form intricate parts of the artist’s creative practice. In this sense, the life of the object continues outside the still-life of the image.

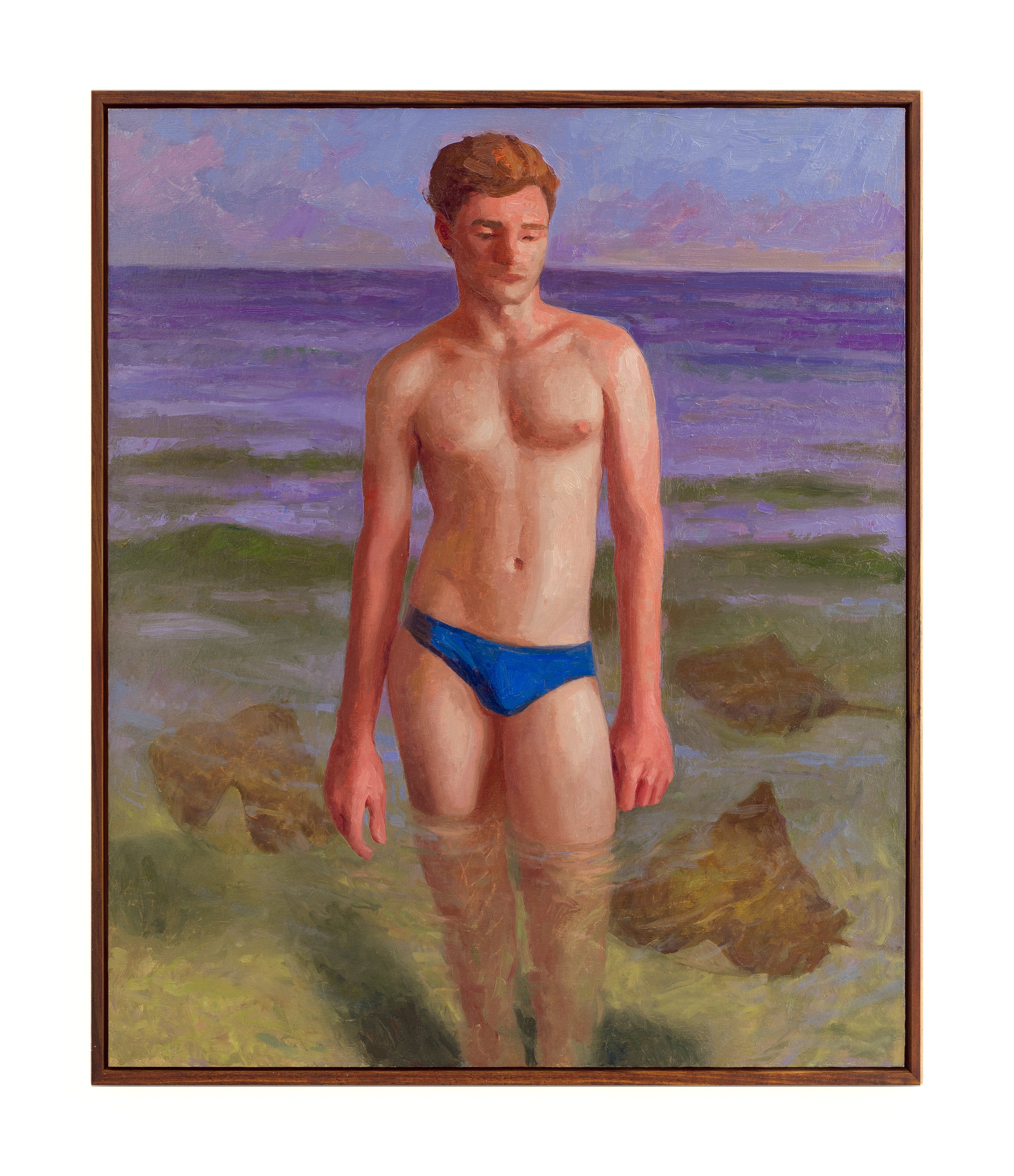

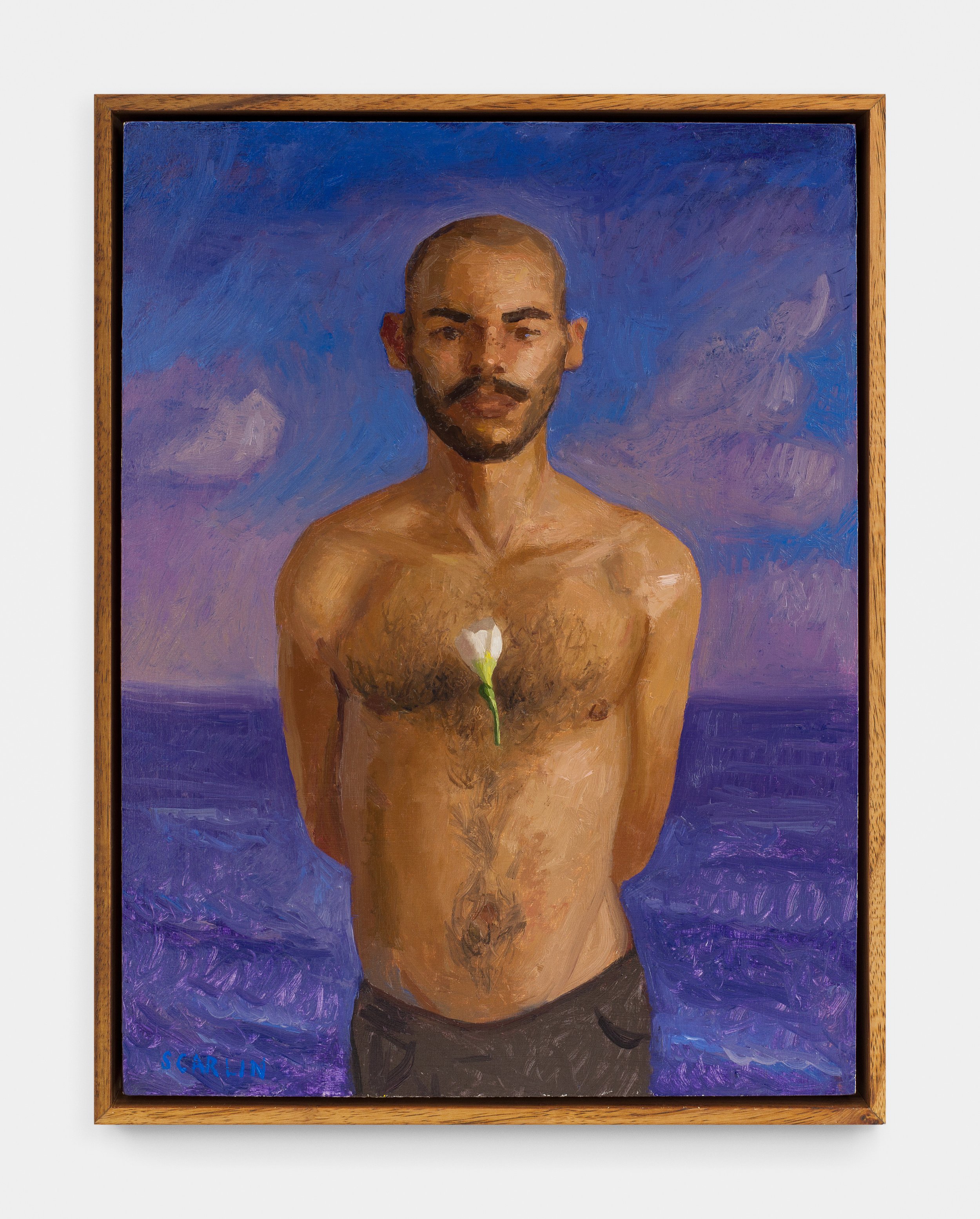

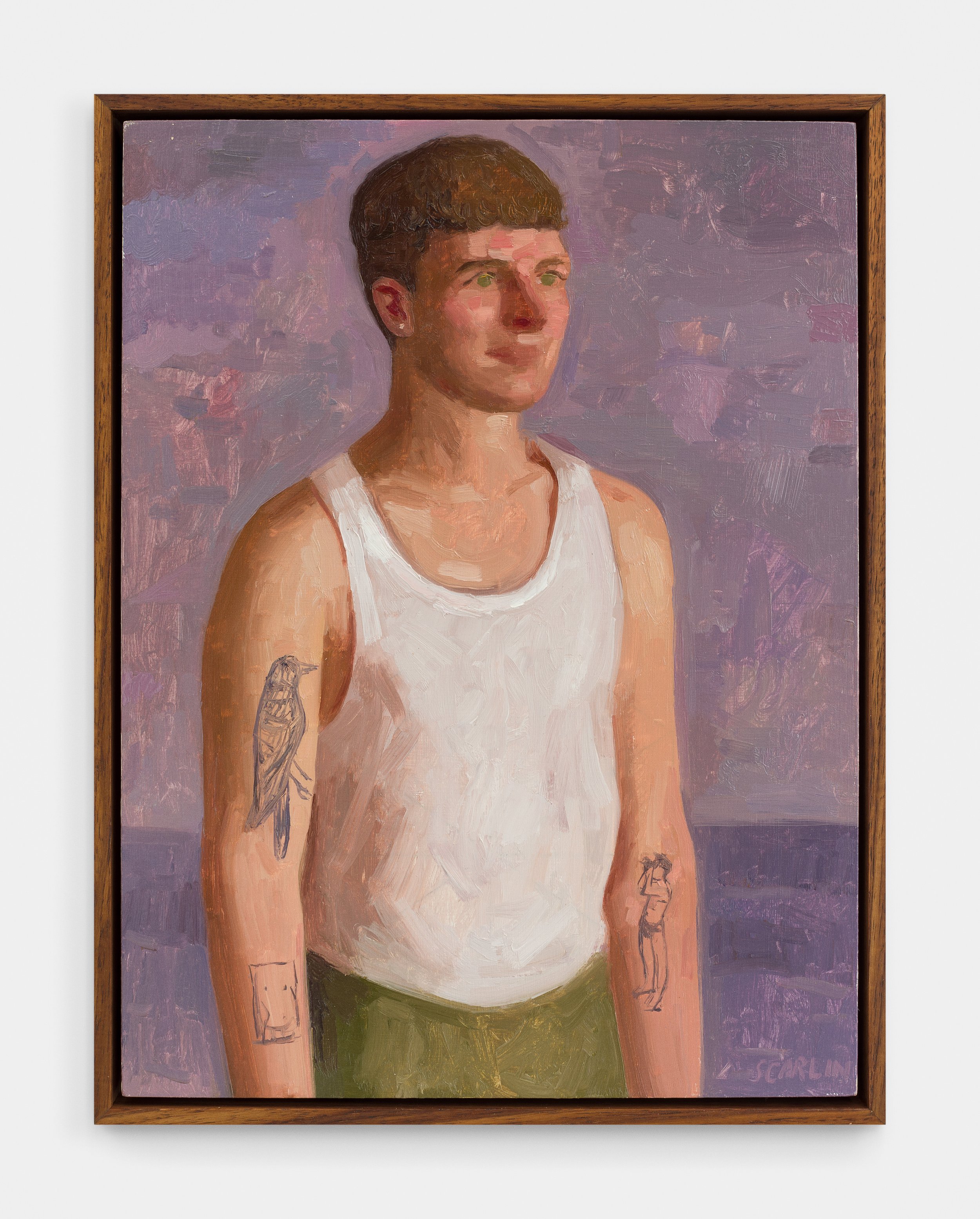

These objects and images, and images of objects, are not speaking to static experiences of life though, but to its fluidity. The ceramic vases and bowls themselves often contain liquids, capturing the kinds of movement and water also found in various portraits and self-portraits. “Harry and the Stingrays” encapsulates this melding of water and movement, while emphasising the vulnerability of the body. Yet, there is a certain defiance in the classic pose surrounded by these beautiful but also dangerous creatures. The scenes of domestic idyll in “Harry reading Armistead Maupin” and the ceramics “Asleep with book” and “Nude, scrolling” sit blissfully beside this scene of precarity, surfacing the sort of subconscious air of dreaminess also found in “Micah and the flower” and “Strauss and the birdwatcher”. The flower, the bird and its birdwatcher, and the floating star in “Two boys and evening star” signal yet another movement from the real towards unearthing a queer subconscious.

It’s also evocative, then, that many of the subjects in Scarlin’s work are queer image-makers themselves. We’re invited to see an unfolding aesthetic vision in the artist’s work, made visible through emblematic horizons that frame subjects in portraits like “On the beach with Shakil”. These images therefore hint at the artist’s evolution towards thinking about domestic intimacy alongside forms of queer world-making. In this sense, the act of creating itself becomes communal and, just like the portraits of other artists, the artist’s partner and friends, the viewer is called to take part in this sense of community.

Text by Ethresia Coetzee